WHY YOUNG LEARNERS SHOULD EXPLORE COMPLEX MATERIAL

"Symbiosis" is a word that few people would expect to hear a 3-year-old say, much less understand. At GEMS World Academy Chicago, an entire preschool unit is built around it.

"Symbiosis" is a word that few people would expect to hear a 3-year-old say, much less understand. At GEMS World Academy Chicago, an entire preschool unit is built around it.

Educators and researchers have long been interested in determining whether students at the early childhood level can understand and benefit from introduction to higher-level academic topics and ideas — everything from complex social concepts to advanced topics in science and math.

The research appears to show that younger students — those in preschool and junior kindergarten, for instance — are quite capable of understanding abstract concepts and complex subjects, as long as those subjects are presented in a clear and relatable way. In addition, introducing this material early improves students' ability to continue learning and acquiring complex knowledge later in their education, and into adulthood.

The research appears to show that younger students — those in preschool and junior kindergarten, for instance — are quite capable of understanding abstract concepts and complex subjects, as long as those subjects are presented in a clear and relatable way. In addition, introducing this material early improves students' ability to continue learning and acquiring complex knowledge later in their education, and into adulthood.

Teachers at GEMS World Academy, a premier private school, agree with those findings.

"Seemingly complex topics become accessible to young learners when teachers are intentional about relating what they're teaching to what children already know," said Joseph Cella, a preschool teacher at GEMS. "This provides children with an opportunity to internalize new and complex concepts."

In a prominent study of the issue, a team of researchers at Boston University found that children actually have an impressive ability to learn and understand advanced scientific ideas beyond their age and current educational level. During their study, the researchers used a familiar vehicle to present a group of children with the basic concepts of natural selection theory: They created a picture book.

The children in the group, ranging in age from 5 to 8, were able not only to grasp how and why the animals in the story were able to develop new traits that let them survive and thrive in a changing environment, they also were able to retain the knowledge and apply it to future learning.

According to Deborah Kelemen, a cognitive developmental psychologist and professor at the College of Arts & Sciences at Boston University and one of the researchers on the study:

We're still astonished by what we found... It shows that kids are a lot smarter than we ever give them credit for. They can handle a surprising degree of complexity when you frame things in a way that taps into the natural human drive for a good, cohesive explanation.

A feature in The Atlantic about teaching complex math to children reached similar conclusions. From the article:

The familiar, hierarchical sequence of math instruction starts with counting, followed by addition and subtraction, then multiplication and division. The computational set expands to include bigger and bigger numbers, and at some point, fractions enter the picture, too. Then in early adolescence, students are introduced to patterns of numbers and letters, in the entirely new subject of algebra. But this progression actually "has nothing to do with how people think, how children grow and learn, or how mathematics is built," says pioneering math educator and curriculum designer Maria Droujkova. She echoes a number of voices from around the world that want to revolutionize the way math is taught, bringing it more in line with these principles.

The article pointed out that using text, pictures, puzzles and games to tap into the "playful" side of mathematics helped young learners understand math concepts previously thought too sophisticated for them, and that such an approach was more effective than traditional "arithmetic" lessons.

The article pointed out that using text, pictures, puzzles and games to tap into the "playful" side of mathematics helped young learners understand math concepts previously thought too sophisticated for them, and that such an approach was more effective than traditional "arithmetic" lessons.

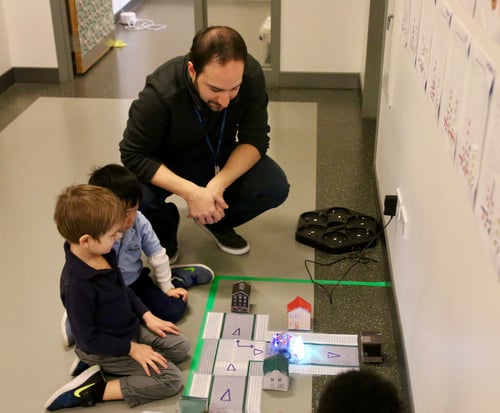

All of this research supports the approach at GEMS World Academy, where early-childhood students go through the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program. Under that framework, preschool students complete the unit on symbiosis; junior kindergarten students explore a contemporary-art museum as part of a unit on materials; kindergartners search for ways to reduce waste while studying waste management; and first-graders raise and release trout into Lake Michigan, a project that bridges units on biodiversity and humans' relationship to fresh water.

Erica Holman, who teaches junior kindergarten at GEMS, said that focusing on students' questions is a big part of her approach to complex material.

"I am continually impressed with children's capacity and high level of interest in tackling big topics," Ms. Holman said. "I always begin an exploration of a new topic by asking them what they know. This allows me to hear their body of prior knowledge and use it as my starting points for further inquiry. I choose things they are most interested in and then we begin building a list of related questions and participating in a variety of hands-on experiences."

By introducing complex material early in a student's education journey, schools like GEMS are better preparing today's young people to be the transformative global leaders of tomorrow.